The Caryatid of the Erechtheion

In the time around 420 BC in Athens, the creation of one of the world’s most classic pieces of architecture was taking place. The Persians had destroyed much of the city during a recent invasion, so Pericles, the general of Athens from 461-429 BC, commissioned two men to restore the damaged buildings atop the Acropolis. Along with restoring the sacred religious building the Persians had destroyed, Pericles also requested that they build another building, The Erechtheion. It was then that Mnesicles, an architect, and Phidias, a sculptor and mason, created what is now known as The Caryatid of the Erechtheion (khanacademy.org; Ross).

Purpose

The purpose for the Erechtheion is lightly debated. Some scholars believe it was built in honor of the mythical King Erechtheus (wikipedia.com) while others believe it to have been built in honor of Athena and Poseidon (Ross). No matter the original cause for it being built, the Erechtheion is a very striking structure that embodies many features common to Ancient Greek architecture.

Unique Features

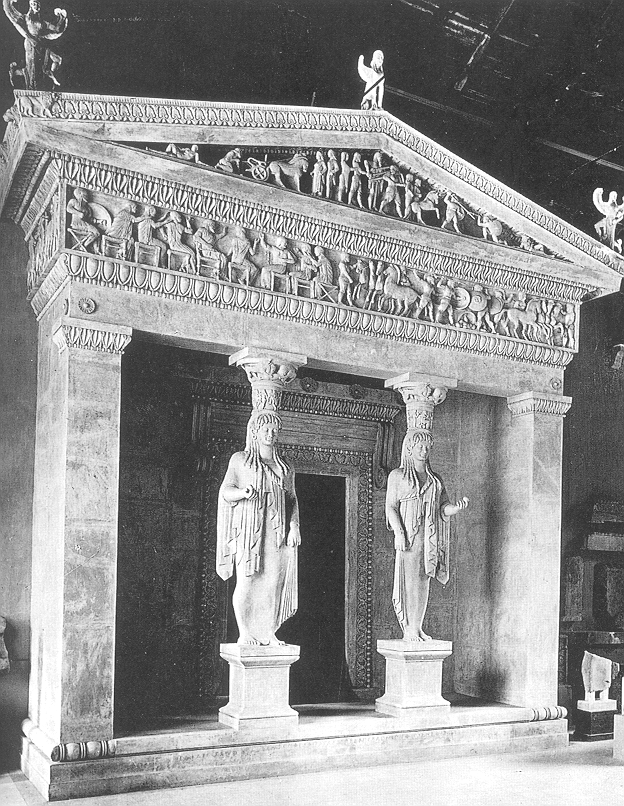

In addition to being a temple built in honor of the Greek Gods, the Erechtheion is also known for the unique pillars holding up the porch on the south side. What is unique about these pillars is that they are shaped in the form of women and are called Caryatids, which is a human figure acting as a column (khanacademy.com). These caryatids were not originally planned for the Erechtheion, but were added to hold up a covered porch designed to hide a support beam that was added to the building after the Peloponnesian War began and caused the building to be downsized due to limited funding (wikipedia.com).

Comparison with Other Caryatid

When the Caryatids of the Erechtheion were created, they were made in a style that was not wholly new to the world. In the 6th century BC, the Siphnian Treasury in Delphi was known to have had caryatids and the term Caryatid was first seen in the 4th century BC (Cartwright). Those previous caryatid, though used in the same manner, did not receive the same notoriety as the Caryatids of the Erechtheion. They were designed in similar fashions, with the “vertical flutelike drapery folds concealing their stiff, weight-bearing legs” (Gardner & Kleiner, 119), but the Siphnian Caryatids were not as realistic and striking as the Caryatids of the Erechtheion.

The Caryatids of the Erechtheion were so much more remarkable than previously known caryatids because they had many features that would soon become the core of the upcoming classical Greek sculpture. Those features include: the intricate folds of cloth, the art of making clothing cling to the body, their realism and the contrapposto pose. These sculptures were covered in cloth that was draped gracefully and set in such a way as to show off the female body without compromising her modesty. The female nude sculpture was not yet acceptable in Greek society, so sculptors devised ways of showing off the female form without the aspect of nudity. The Caryatids of the Erechtheion showed off the legs, body and breasts of the female form in an idealistically realistic, yet modest, way as to make them significant and noteworthy to those who came to see them.

Conclusion

The Caryatids of the Erechtheion are important to Greek architectural history because they embody the form of the ideal woman to the Ancient Greeks and they “display features which would become staple elements of Classical sculpture” (Cartwright). These statues celebrate the ideal female form while showing off the intricacy of the design needed to form them. The features of the Caryatids of the Erechtheion would soon become common across the Greek architectural community and a classic representation of the art of that age.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alderman, Liz. “Acropolis Maidens Glow Anew.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 07 July 2014. Web. 19 Sept. 2014. <http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/08/arts/design/caryatid-statues-restored-are-stars-at-athens-museum.html?_r=1>.

Cartwright, Mark. “Caryatid.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 29 Oct. 2012. Web. 19 Sept. 2014. Caryatid/>.

“Caryatid from the Erechtheion.” The British Museum. The British Museum, n.d. Web. 19 Sept. 2014. <http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/gr/c/caryatid_from_the_erechtheion.aspx>.

“Caryatid.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 19 Sept. 2014. Web. 19 Sept. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caryatid>.

Clair, William St. Lord Elgin and the Marbles. London: Oxford U.P., 1967. Print.

“Contrapposto.” Khan Academy. Smart History, n.d. Web. 19 Sept. 2014. <http://smarthistory.khanacademy.org/contrapposto.html>.

The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Caryatid (architecture).”Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d. Web. 19 Sept. 2014. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/97646/caryatid>.

The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Contrapposto (art).” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d. Web. 19 Sept. 2014. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/135385/contrapposto>.

Gardner, Helen, and Fred S. Kleiner. Gardner’s Art through the Ages: The Western Perspective. Boston, MA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2010. 99. Print.

Harris, Dr. Beth, and Dr. Steven Zucker. “Caryatid and Column from the Erechtheion.” Khan Academy. Khan Academy, 1 Oct. 2011. Web. 19 Sept. 2014. <https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/greek-art/classical/v/caryatid-ionic-column-erechtheion-421-407-b-c-e>.

Shear, Ione Mylonas. “Maidens in Greek Architecture : The Origin of the « Caryatids ».” Bulletin De Correspondance Hellénique 123.1 (1999): 65-85. Web.

9 Comments

Pingback:

Pingback:

Diatta @ Femme Fitale Fit Club

This is gorgeous! I want to travel more in the coming year – there is so much to see out here. I loved reading Greek mythology as a child in 2nd grade.

Carmen Perez (Listen2 Mama)

I love Greece and we have visited the Acropolis several times, great post!

Jessica Jones

I love reading posts like this. My husband and I are both really interested in history and Greek mythology and stuff like that. Thanks for posting!

GiGi Eats

Greek and Roman history – my favorite, well I also love Egyptian….. Ah I just LOVEEEEEEEEEE history! I visited Turkey a few years ago and died from excitement!

christine

Great info!

Diana

I’m constantly amazed about how we are able to know so much about what happened in the past and have things from so long ago still existing today.

Kim

History was one of my favorite subjects in school so it was cool to read about greek architecture and a bit of history behind the Erechtheion